When did saving the planet become an emergency? Apparently December 2016, when Darebin, Melbourne decided regular climate action wasn’t cutting it anymore. They declared the first climate emergency. Now over 2,100 local governments across 39 countries have joined the party, covering more than a billion people who presumably enjoy having a livable planet.

The terminology matters. Scientists and politicians love their declarations—it’s formal recognition that humanity’s climate situation has gone from “concerning” to “oh crap.” The UN calls climate change a borderless global emergency. UNEP wants everyone shifting into “emergency gear.” Because decades of polite suggestions worked so well.

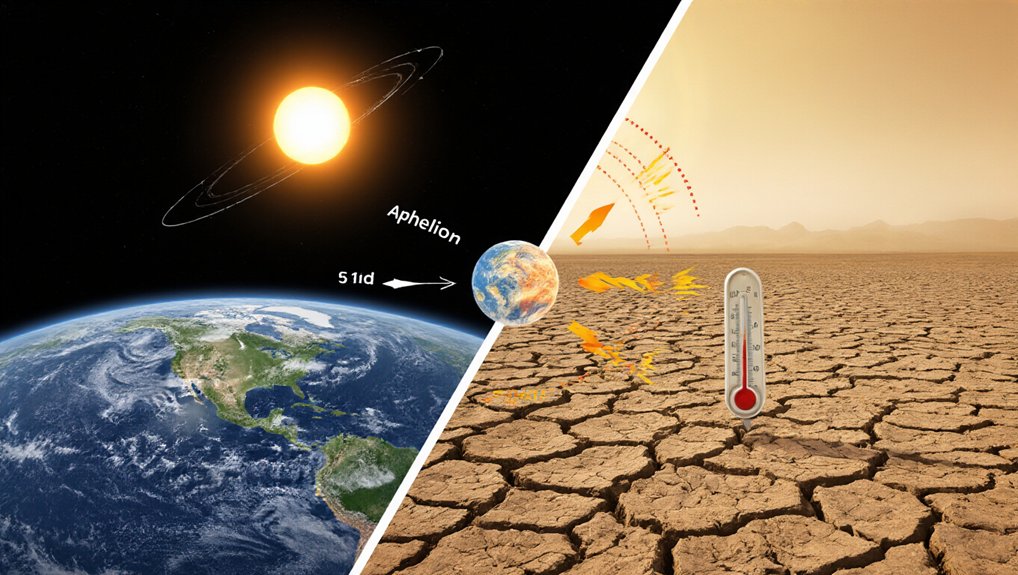

Here’s the thing: global temperatures keep climbing past that 1.5°C Paris Agreement target. Remember that legally binding promise nations made? The one about keeping warming below 2°C? Yeah, about that. Countries are required to submit updated national climate action plans under the Paris Agreement, but even those aren’t ambitious enough. Meeting the Paris Agreement goals requires halving greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. Developed countries’ emissions aren’t dropping fast enough. Actually, scratch that—global CO2 emissions are still rising. Fossil fuels remain the star of this horror show, with industrial, agricultural, and transportation sectors pumping greenhouse gases like there’s no tomorrow. Which, ironically, there might not be.

Wales jumped on board in April 2019, becoming the fourth country to declare a climate emergency. These declarations acknowledge what everyone already knows: current measures are laughably insufficient. The systemic failure is so obvious that some folks are already talking about accepting higher warming limits. Because giving up is always an option.

Public opinion’s catching up. A UN survey found 64% of 1.2 million respondents across 50 countries consider climate change a global emergency. The emergency framing helps—it pushes policy directions, mobilizes resources, influences democratic processes. Growing climate activism demands stronger language because apparently “pretty please stop destroying Earth” wasn’t working.

Post-declaration, governments typically prioritize emissions reduction and climate adaptation. Some integrate emergency status into legal frameworks. Policy shifts emphasize both mitigation and adaptation—reducing emissions while preparing communities for impacts. It’s multitasking on a planetary scale. The escalation of extreme weather events is making these adaptation efforts increasingly urgent as communities worldwide face unprecedented challenges.

The climate emergency isn’t coming. It’s here. Over a billion people live under governments that officially recognize this fact. The question now is whether emergency declarations translate into emergency action, or if they’re just more hot air in an already overheated atmosphere.